The immortal poet and writer of human condition, the Lebanese American Kahil Gilbran once wrote; “The deeper that sorrow carves in your being, the more joy you can contain”. There is a truth, sadness shapes the contours of our soul, and our mental character in a fundamental way. Just as an engraver uses force to carve incisions on a stone, thereby creating an object of beauty, so our suffering makes each of us the unique individual who we are. Gilbran suggests that there is a deep connection between sadness and joy. It is in our sadness that creates the space for happiness to flow through, in the same way that an empty stage allows actors to sparkle in their element. It is only in the backdrop of darkness that the stars are able to shine forth and the brightness of dawn is so welcome.

Countless people have taken solace in the idea that the darkest hours come just before dawn. Like everything else it will pass bringing a brighter morning. Only when we are touched by sadness can we truly realize the true value of happiness. Going further still, Gilbran articulates the uplifting idea that the deeper the sadness we have endured, the greater joy we are able to feel.

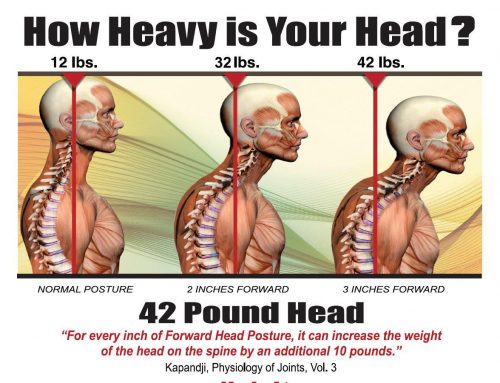

In speaking about the virtues of sadness, I must right away emphasize that I am not talking about depression, which is serious, damaging, debilitating illness. Indeed the wealth health organization has made the troubling forecast that depression will be second on the list by the year 2020. Of course the water becomes murky when attempting to differentiate between sadness and depression as the two emotions overlap in many ways. Sadness is a normal aspect of human condition. Then if it becomes suffiecntly intense or prolonged it may cross the line and pass into depression.

Unless you are depressed it is important to see that normal sadness as not as an illness but as part of our common humanity.

When normalizing sadness in this way it is a natural response to circumstances such as bereavement. Gentle reminders from the universe that can help us have a certain amount of acceptance – both for the loss of itself and of sadness of the correct response. The Buddha adopted this stance over 2500 years ago, amend a similar approach has given solace to hundreds of millions of people ever since, both Buddhist and non-Buddhist.

A grieving mother, Kisa Gotami, suffered the ultimate pain of losing her child. In desperation she asked the Buddha for medicine that miraculously might bring her child back to life. With compassionate wisdom, the Buddha said he could help. He asked kiss to bring him a handful of mustard seeds, but made the stipulation that the seed must be from a home where no one had lost any loved one.

Kisa went from door-to-door hoping to come across a household that had never suffered such a loss. Of course every family had its own tale of woe, which they shared with kisa, forging connection in their shared sense of loss. This did not lessen kisa grief, but it did usher her into communion with others who had been left similarly bereaved, showing her that it was only human to grieve. She eventually attained a measure of acceptance about her loss, and understood that death is woven inherently into the fabric of existence.

In cultivating acceptance in this way, Buddhism speaks of ‘two arrows’. When we lose someone, we erase pierced by intense grief. This or any type of hurt is the first arrow, which is wounding enough in itself. But all too often we recoil against that initial reaction and start to feel sad about feeling sad (or in another context, start to feel angry about feeling angry). The secondary response – known in psychology as a ‘met emotion (that is an emotion powering an emotion) – is the second arrow. It can be just as hurtful as the first, and sometimes even be more damaging. It may be well impossible to remove the first arrow, to temper that sense of loss or hurt we feel in such experiences as bereavement. However if we can mange to accept our feelings – perhaps by seeing them as burdens we must all carry at some point in life – we can at least make peace with them and remove the second arrow.

We do not have to be Buddhist to appreciate this notion of the two arrows. Indeed Buddhism ethos of acceptance is emphasized in almost every religion tradition plus in spiritual and therapeutic discourse more broadly. Read my article here ‘Buddahs second arrow’.

Even if we retreat sadness as normal, how about we make peace with this emotion, we might still regard it as an invidious, unwanted emotion.

Once we accept the presence of sadness in our lives, we can learn to appreciate it to some extent. We can realize that despite it’s melancholic appearance, it can play a useful role in helping us to lead full and fulfilling lives. Essentially we become sad mainly when the people, places and objects we care about are threatened hurt or lost. Seen in this way, we realise that sadness is an expression of love and care.

Sadness is a rehabilitee phase of protection and recovery and serves to elicit help. By entering hibernation, we are also afforded an opportunity to take stock and revaluate events and choices that brought us to this low place in the beginning.

Sometimes we must need to stop in our tracks and ask some vital questions. Where am I going? Is this the right path for me? Why have I been marching this way? Having stopped, exhausted and vunerable, we may even spot some fresh paths of undergrowth which we would have strode straight past during the normal headlong dash through life. We see things we have never noticed before, and are gifted insights into understandings that were previously obscure.

Bibliography

The positive power negative emotions Dr. Tim Lomas